Very little data is available describing the lives of the African slaves of Indian Territory. However, an often over-looked source of data comes from the

Indian Pioneer Papers, that interviewed early white, black and Indian Citizen about their lives and their families. Many of the people interviewed often related stories of what they knew of slaves, owned by their own family, or referred to some of their former slaves who were still living.

In the case of Chirstine Bates (nee Folsom) she spoke about her life in the Choctaw Nation, and how her father, a preacher eventually amassed property and including 50 slaves.

She describes the perils of life during the Civil War, and she then mentions of of the former slaves by name. Lindy Butler was one, who Ms. Bates recalled, and she pointed out that Lindy, the slave had born 21 children. One of the children was still living at the time of the interview (in the 1930s)

Well, as a genealogist and researcher, I became interested in Lindy Butler and her children. How amazing that she was able to bear so many children while she was a slave. She undoubtedly contributed to the wealth of the slave master significantly, as her children, her issue would have belonged to him. Unless of course they were leased out to another family as often happened with slaves---they could be given away or rented or sold at the whims of the slave owner. Lindy was probably long deceased in the1930s, but there was a reference to one of her children---Ed. And Ed, as one of her children, was probably only a small boy by the time that emancipation came. The fact that the daughter of the slave owner was aware of not only "Aunt Lindy Butler" but that she knew what had become of at least one of her children, suggests that all contact might not have been hostile after freedom came.

So, could I find Ed in the records? As the son of a Choctaw slave, he would have been a Choctaw Freedmen himself. Could I find his file?

I began to search to find Ed Butler, son of Lindy Butler, a Choctaw slave.

Using the Native American CD, created by the Friends of OHS that contains a searchable database of all Dawes Rolls enrollees, I examined the surname Butler. There were 2 possibilities. Two Freedmen were named Ed Butler.

Either of the two Eds could have been, the right one, for both were in their 40s. Either might have been the son of "Aunt Lindy", the slave. In addition both of those men, were clearly put on a Freedman Roll, because there was a policy--even if the former slave had the blood of the slave owner---the data was not to be shown. (This policy now contributes to the exclusion policy practiced by the 5 slaveholding tribes to this day. The years of forced labor meant nothing, then and now, and those with documented ties to the tribes, if they are African slave descendants, are they are forbidden admission to the nation where their ancestors lived, toiled and died.)

Considering therefore, that it was decided during the Dawes Enrollment years to never include data about any Indian parentage if the person had any Negro blood, to find the right Ed, (son of Lydia) in this case meant a careful examination of the records was required. Seeing the names of these two "Eds" on the Dawes Rolls with the blood category being left blank, meant therefore, that they were indeed Freedmen. But Freedmen from which tribe?

I looked first at Ed Butler on Card 1039. Going farther into the database indicated that he was Choctaw Freedman.

Could I find him among any records? Could Ed, the Choctaw Freedman be Lindy Butler's son? I had to examine his Dawes Card.

Enrollment Card of Ed Butler, Choctaw Freedman

At first glance this might not have been the right Ed Butler. He was a former slave, in the Choctaw Nation. He lived in Atoka and was enrollment with his children. However, the card states that he had been enslaved by someone called, "Mrs. Robb. Hmm........the reverse side of the call would have more information.

Side 2 of Enrollment Card of Ed Butler, Choctaw Freedman

On this side, information pertaining to the parents of Ed Butler can be found. His father's name was Lemon Butler. His mother's name was Linda Butler. Linda-----as in Lindy?

If Linda was possibly the same Lindy-----then this was one of her 21 children!!!

BUT----who was Mrs. Robb?? I then realized that many times children and their parents did could have had different owners. And in the case of a woman who may have been widowed--remarriage before her death could have occurred, also. So Mrs. Robb is a mystery. But there was another clue---Israel Folsom, the slaveholder.

Known in the Choctaw community, to be an ordained minister, Israel Folsom was a man of prominence in Blue County, where he lived. I was surprised to also find an image of him, actually several images of him.

Israel Folsom

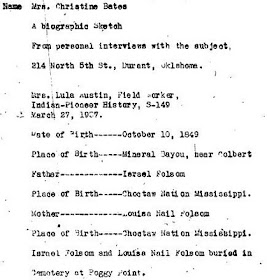

Enrollment Card of Christine Bates, interviewee

of Indian Pioneer Papers and daughter of Israel Folsom

I had to also stop and reflect. Israel Folsom had a relative--possibly a cousin---Joel Folsom. Joel Folsom was the son of Solomon Folsom, also in the same clan of Choctaw Folsoms. I mention Joel only because he married Emeline Perry--whose family was the slaveholding family of

my ancestors.

Biographies of Israel Folsom, indicate that he was well respected by most who knew him, and one can only hope that the fate of his slaves was not one of harsh treatment or misery.

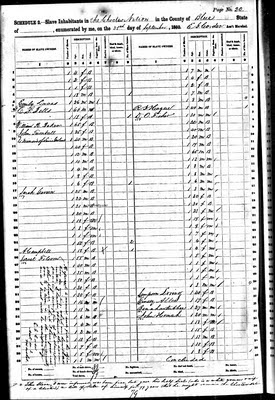

At the time the census enumerators came into his community to count the slaves to put on the Slave Schedule, it does appear that he was not cooperative and the census enumerator had to obtain information on his slaves from others. (See note on side panel, below.)

Slave Schedule 1860, Blue County, Choctaw Nation

Note made alongside that of Israel Folsom

Side Panel of Nation, pertaining to the slaves of Israel Folsom

I was pretty confident that I had found the right Ed Butler, son, of Linda (Lindy) Butler, who was a slave of Israel Folsom. But---there was another Choctaw Freedman with the same name. To be sure, it was imperative that I investigate the other Ed Butler, as well. It was evident that the other Ed Butler was not the son of Lindy, slave of the Folsoms. this Ed Butler was enslaved by another leading Choctaw---Peter Pitchlynn.

Ed Butler, former slave of Peter Pitchlynn

It also appears that the parents of Ed Butler were also Pitchlynn Slaves.

Reverse side of Ed Butler's Enrollment Card

reflects his parents who were both enslaved by Peter Pitchlynn

So, I had found in the records, Ed Butler, son of Lindy Butler. I only hope that in his lifetime, his fate and that of his children were remarkably different. By statehood, they would have been entitled to schools, and a few more opportunities. Did they remain in the region after statehood?

The descendants of Ed and Lindy will have to tell the rest of that story. Hopefully someday they will discover their history and tell what happened to the next generations.