And so goes the ruling made August 30, 2017 in favor of the Cherokee Freedmen.

For many this ruling is a surprise---Cherokee Freedmen, descendants of the formerly enslaved people held in bondage, have been struggling for the greater part of the past century for their rights to remain citizens in the tribe of their birth, and the tribe of their ancestors. Over the years there have been continuous efforts for the Five Slaveholding Tribes, to cleanse their nation of the presence of descendants of their slaves.

In the Cherokee Nation, during the tenure of the first female Principal Chief, Wilma Mankiller, the Freedmen began a decades long saga fighting for their rights to remain citizens, after having been kicked out of the nation. Some who had been a citizen for their entire life showed up to vote to suddenly be told that they were no longer citizens.

This happened in 1983, when Rev Robert Nero, an elderly man showed up to vote in a Cherokee election. He had voted in other years including the previous election in 1979. He was told that he could not vote because he did not have "Cherokee blood".

For many with roots in the deep south, this is similar to many African American citizens who were prevented from voting, because their "grandfathers" had not voted. For others this treatment was not different from the challenges made to other blacks by giving them exams that were not passable, again to prevent their voting and sharing in the rights as citizens.

In 1984, Rev Nero and others filed a class action lawsuit challenged this new policy. They stated that their treatment by the tribe had been "humiliating, embarrassing, and degrading." The tribe argued that the Federal court had no jurisdiction in the case, as it impinged on tribal sovereignty. That case went on and ruled in favor of the tribe. The Appeals court ruled that the case was a tribal issue and allowed the lower court ruling to stand. That ruling occurred in 1989--5 years after the case was initiated.

This began a saga again and that would emerge, would challenged next time when Bernice Rogers Riggs, a descendant of slaves one held by the family of noted humorist Will Rogers, challenged the issue. Her case was somewhat different, because she challenged the issue in Cherokee Court and not Federal Court. At that time I was contacted by one of the attorneys representing her to be a witness in her case. That was in the summer of 1998, in the capitol of the Cherokee Nation in Tahlequah.

Mrs. Riggs sued Lela Ummerteskee the tribal registrar, over her having been denied citizenship in 1996. She had documented her family ties to the nation, but she was denied enrollment because her ancestors were placed on the Freedman Roll

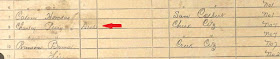

This long standing policy of forbidding enrollment of those whose ancestors were on the Freedmen Roll, has been a long standing policy, deemed acceptable by many for years. The policy of allowing those who are caucasion with 1/1000th degree of Indian blood, based on a flawed roll that intentionally ommitted any blood degree of any kind on Freedmen, has been an on going issue. Basically those who ancestors were enslaved by those who marched alongside their slave holders on the same Trail of Tears, have basically been told repeatedly that their blood didn't count. Yet---Freedmen descendants can prove that they descend directly from their ancestors on the Dawes Rolls. This is the same roll that will admit those who descend from Inter-married whites, whose degree of Indian ancestry is minuscule, and if a DNA test were issued, they would have little to no Indian DNA showing. But DNA is not an admissible element for citizenship. Admission is based on having ancestry of a certain portion of the Dawes Roll.

Over the years, more individuals became aware of their own ties to the Five slaveholding tribes. In 1991, I discovered my ancestors on the roll of Choctaw Freedmen. I learned that my own great grandmother whom I had known when I was child, had been born enslaved in the Choctaw Nation. I found her enrollment card and was stunned when I saw my own family and beside their names a column headed by the words "slave of" followed by the name of the slave holding family.

Two years later I wrote a book about researching the Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, published by Heritage Books. Astonishingly this was the first book ever written as a genealogy guide for the thousands of Freedmen descendants. I began to meet others from around the country, who had roots in Oklahoma, and who could also document their history to that of the Freedmen. I began to study the history of slavery in the Five Tribes and was learning an incredible history never taught and still not taught in Oklahoma schools. The history ommitted, is that slavery occurred in the land that became Oklahoma.

I also learned about the fact that Freedmen had been kicked out of the tribe, and that the nation had basically looked away, while people with documented ties, were not allowed citizenship in the nation which was part of their own family history. I also learned the policy was one where those with ancestors on the rolls of "Blood" and "Inter-married whites" are admitted into the tribe, and those with ancestors on the rolls of "Freedmen" were not allowed. I learned also that they have been excluded steadily for the past 3 decades.

However, the last decade has brought about more challenges with some changes. In 2001, Marilyn Vann sued the nation once again after she was denied enrollment, because her father and grandparents were on the Freedman Roll. Ms. Vann and others challenged the ruling and this time, others became aware of this new challenge, and began to show their support. The Freedmen were admitted by the Treaty of 1866. Among the new supporters of the treaty were the Delawares who were adopted by the same Treaty. They showed support of the Cherokee Freedmen.

Three years later, in 2004 Lucy Allen, another Cherokee Freedman descendant filed a case in Cherokee court, claiming that the exclusion of Freedman was unconstitutional. It should be pointed out that the first line in the Cherokee Constitution states that "The law of the United States is the law of the land". The Appeals council ruled in favor of Lucy Allen's case, thus opening the doors of many Freedmen descendants to then apply for citizenship.

Then a ruling was made in 2006 overturning the earlier ruling against the Freedmen. This began a back and forth issue of allowing the Freedmen to enroll, followed by Cherokee Chief Chad Smith calling for a vote to expel the Freedmen. Only 3% of the eligible voters participated in the vote, which came out as a vote of expulsion. The tribe officially claimed that over 70% voted to expel the Freedmen, though it was 70% of the 3% who had voted.

In 2012 a case was filed in 2012 with the Cherokee Nation claiming that it was not required to admit the former slaves as citizens. There was a counter suit and it was decided to combine the cases since both cases involved the exact same parties. In May of 2013 a hearing was held in Federal Court in Washington DC. I attended that hearing and had a chance to observe as attorney Jon Velie argued on their behalf.

Today, August 30th a ruling by Thomas F.Hogan, senior United States District Judge. He ruled that Cherokee Freedmen have rights guaranteed to them as full citizens, as the treaty promised. The treaty he referred to was the Treaty of 1866.

It will never be known why it has taken years for this case to be settled. There was hope that the ruling would have been much earlier, but at last a ruling has been made. It is not known how other tribes will act in light of this ruling. The language of the treaty is clear. Hopefully with this ruling, I can only hope that others will now start to pursue their history and genealogy with vigor and enthusiasm. The nation has come to terms with the unequal treatment of one part of the nation in light of the trial and of the analysis.

Perhaps the tenacity of the Freedmen beginning with Rev. Nero and their unwillingness to disappear quietly was something that was never expected. It is stated that the tribe spent millions of dollars trying to remove the descendants of their slaves from the nation. Based on race and color, although many descendants could actually prove that they too had Indian blood, the fact that the Freedmen never quit the battle was never expected. Principal Chief Chad Smith who vehemently sought to purge the Freedmen from the nation, is no longer in office, and the Freedmen whom he wanted removed, have now won their case, once again, and as in previous cases, it was decided upon the merit. The Cherokee Freedmen were citizens and are citizens of the nation.

There are more than 20,000 genealogy files pertaining to the Freedmen that are genealogically rich and historically significant records.

The numbers of Freedmen descendants from all five tribes is significant, especially if one looks at the numbers from 1906 when the Dawes Rolls were still being developed:

Cherokee Freedmen 3982

Choctaw Freedmen 5254

Chickasaw Freedmen 4995

Creek Freedmen 5585

Seminole Freedmen 857 (+93 children born later)

Total number of Freedmen from Indian Territory: 20,766.

My hope is that others will step further to examine their history more intensely.

Meanwhile, the work and tenacity of the Cherokee Freedmen, with leader Marilyn Vann are to be recognized. Their courage to address racially based treatment of them over the years has been observed by all, and their battles have caught the attention of historians and scholars throughout the nation.

Meanwhile, the work and tenacity of the Cherokee Freedmen, with leader Marilyn Vann are to be recognized. Their courage to address racially based treatment of them over the years has been observed by all, and their battles have caught the attention of historians and scholars throughout the nation.

They have been peaceful and maintained their dignity over the years as efforts were made from tribal leaders to attorneys to lobbyists, to discredit them, and their plight. Hopefully this will bring to an end the saga begun in 1894 when Rev. Robert Nero challenged those who had once enslaved his parents and grandparents.

Our job now, is to assist others as they seek to tell their story. The Oklahoma Freedmen have an incredible story to tell!