They are the grandchildren of Sallie Walton, through her daughter Louisa, who was on Choctaw Freedman card #777 with the rest of the Walton family.

Choctaw Freedman Enrollment Card #777

The National Archives at Ft. Worth Texas 1868-1914, NAI Number: 251747

Record Group Title: Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75

Among some family records an old photo was located taken at a small country school in the Choctaw Nation. Easter Sanders identified who her siblings were before she passed away in 1999.

Sanders Children in Old Family photo

Personal Collection

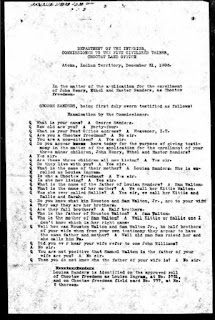

The Application Jacket

The first items found in the application jacket were three birth affidavits for each of the Sanders children. John Henry, Ethel and Easter Sanders all had birth records that were recorded. A surprise for me was to learn that my great grandmother Sallie was listed as the midwife attending the births of her grandchildren.

National Archives Publication M1301, Applications for Enrollment

(Also accessed from Fold3.com, Native American Collection, Choctaw Freedmen

Questions were also asked regarding Louisa's mother Sallie. In that exchange a references was made to a nickname that they used for Sallie. Sometimes they called her "Kittie".

Upon reading about her nickname I personally recall an uncle visiting the home speaking with Sallie, and him asking her "didn't they used to call you Kitty?" I remember that conversation from my childhood only because I thought it so odd. I recall that she did not reply, but she simply smiled at him, when he called her that name.

(I would only learn later that "Kitty" was also the name of her grandmother--her mother Amanda's mother's name was "Kitty Perry." I would also learn in a court document when Nail Perry would state that Kitty was sometimes called "Old Kit".)

Upon reading about her nickname I personally recall an uncle visiting the home speaking with Sallie, and him asking her "didn't they used to call you Kitty?" I remember that conversation from my childhood only because I thought it so odd. I recall that she did not reply, but she simply smiled at him, when he called her that name.

(I would only learn later that "Kitty" was also the name of her grandmother--her mother Amanda's mother's name was "Kitty Perry." I would also learn in a court document when Nail Perry would state that Kitty was sometimes called "Old Kit".)

Again the questions would drift back to the identity of Louisa's father.

There was some concern whether papers had been submitted on time to enroll the children. George Sanders pointed out that he did mail in papers for Ethel and they had been submitted many months before. They became part of the official file as evidence for the case.

(Same as above)

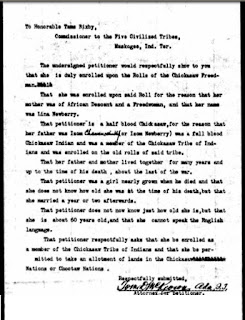

It appears that in spite of the mother's status as an enrolled Choctaw Freedman, the fact that a deadline had been missed, put the children in jeopardy of being enrolled as Choctaw citizens. The stipulation was focusing on submission of an application for the children prior to November 1906 and even the evidence submitted on Ethel's behalf, the case was denied. Appeals were made but the decision made "adverse" to the applicants was upheld.The Sanders family still had access to land that was obtained through the enrollment of Sam and Walton, and Louisa's brothers Houston, and Sam Jr. For many years, this Sanders lived in what became Le Flore County Oklahoma, around Heavener Oklahoma as George the father worked in the mines. He and Louisa raised their children in Le Flore County, where they remained well into the 1940s.

Their close cousins the Waltons had moved into Fort Smith to obtain high school education for the Walton sons, Samuel Louis, and Richard Daniel . They, like the Sanders remained in Fort Smith. And meanwhile, another branch of the Sanders line moved to Bakersfield California where they remain to this day.

Descendants Today

Through Bennie Sanders and daughter Ruthie Sanders Bradley, the family continues to thrive in Western Arkansas. Through George Sanders Jr., the line continues through the families now based in Bakersfield California.

Within various families branches of the extended family, the ties to the cultural base in which they lived remained strong. Sallie, the family matriarch was always known to be Choctaw, as she spoke the language, and practiced many cultural traditions. Many of her great grandchildren from both Sanders and Walton branches, recall her teaching them words and phrases in Choctaw. Her brother "Uncle Joe" would occasionally visit the family in Arkansas, and some elders still recall his visits.

Ethel, the one of the daughters of George and Louisa died as a young girl at the tender age of nine years. John Henry lived to adulthood, and worked as a mechanic for Texaco in Poteau Oklahoma for most of his life with his wife Augustus Sanders a popular school teacher in the black school in Poteau. Easter Sanders lived to be 91 years of age and died in 1999 in McAlister Oklahoma.

The family always knew and spoke of their Grandma Sallie and considered her to be a traditional Choctaw woman. Cousins in California who descended from George and Louisa throughout the years spoke of having been denied their rights as Choctaws, since their mother Louisa had been enrolled.

I first made contact with some of the California Sanders cousins who descended from George Sanders, one of the younger children of Louisa and George. Their father George had asked in his final days that they continue the family's quest to prove their Choctaw history.

There is no land to obtain now, and admission to the nation will not come to them, but through history, their history and documented tie to the land of their father's birth has been completed. Born of the Choctaw Nation, their roots are already proven, and hopefully they will find peace knowing that their ties are there and cannot be denied.

-John Henry, Ethel, Easter, and later George and Ben were the children of George and Louisa Ingram Sanders.

-Louisa was the daughter of Sallie Walton

-Sallie was the daughter Amanda Perry.

-Amanda was the daughter of Kitty Crow

-Kitty whose parents are unknown came with the Perrys clan from Yalobusha County Mississippi on the Trail of Tears.

Kitty was the oldest person enslaved in the Perry clan, and Kitty, Amanda, and Sallie would not see freedom until 1866. Their ties to the Choctaw Nation before and after removal are strong and are well documented and the descendants of all from George Sanders Sr. to Ruthie Sanders Bradley can know that their history is strongly rooted upon the soil, and upon the pages of history.

These families are important to me, because they, like myself, all descend from Sallie Walton. Our legacy is a strong one, and status on the roll or not--we have a history that deserves to be told, to be honored and to be celebrated.

This is the 52nd article in a 52 article devoted to sharing histories of families once held as enslaved people in Indian Territory, now known as Oklahoma. The focus has been on the Five Civilized Tribes, and these posts have been part of an ongoing project to document 52 families in 52 weeks.