The family of Betsey Mahardy of the Seminole Nation presents a very complicated and complex family from Indian Territory. The story is complicated not because of size, but because of the family's personal identity of itself, as well as the official label placed upon them. It is complex because of the many "types" of lives lived by the family and the generation that preceded them.

The family story is one of a family of free people of color, of enslaved people, of those who intermarried between tribes and of Africans who also had spouses who were Indians as well. The case also includes one of identity and affiliation that will be reflected in one of the more extensive interviews that can be found.

Betsey Mahardy and her family resided in Wynnewood, Indian Territory in the Chickasaw Nation. An application was made in 1899 in front of the Dawes Commission to enroll Betsey and her children as Seminoles. It was stated that she belonged to the Ceasar Bruner Band of Seminole Freedmen. She was 57 years old at the time and had once been enslaved by Seminole Sam Bruner.

Her sons were Richard Bruner, Samuel Mahardy and Lyman Mahardy. Betsey's parents were Charlie Stedham, and Eliza Canard. Her father was once the slave of Sallie Stedham, and her mother was a slave of Seminole Wiley Canard.

Her first husband, the father of her son, Richard Bruner, was Sam Bruner, a Seminole Indian, and thus, always free. He had died during the Civil War. Her second husband was Wyatt Mahardy, the father of her other two sons. The question arose when their son requested to be transferred to that as Chickasaw by blood. That would become the focus of much discussion that will be illustrated in the application jacket and series of complicated interviews to follow.

However, it should be noted that on the front of Betsey Mahardy's enrollment card, it was noted that Wyatt Mahardy was actually a Chickasaw by Blood. The reverse side of the card reflects that he was born free and had not been enslaved.

And, most interestingly, on the enrollment card itself, there was a clear boldly written notation that explains the entire issue---Betsey Mahardy was married to a man who was not Seminole, but actually Chickasaw. But the note from the commission on the card, pointed out that though he was Chickasaw,

"his father was a Negro."

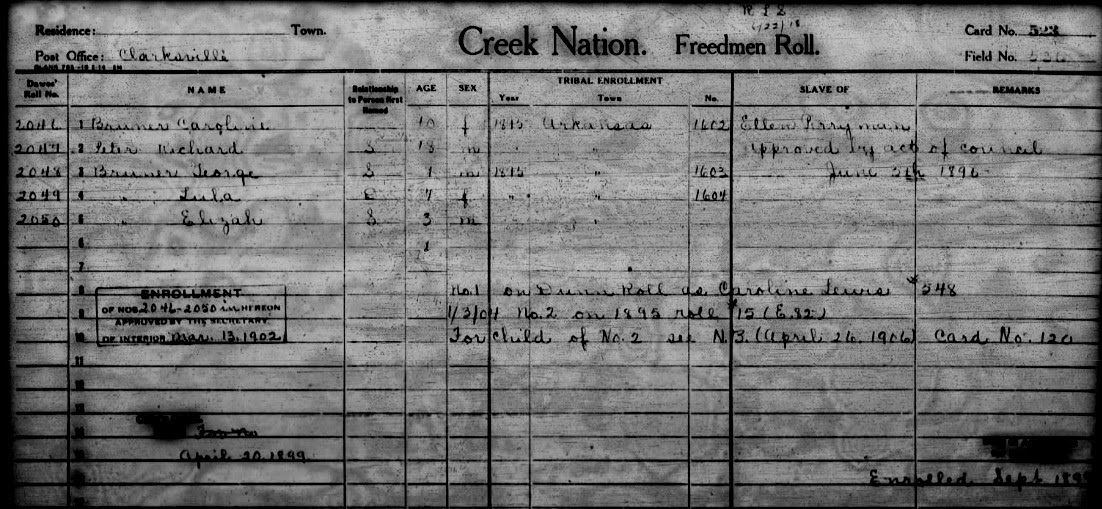

The National Archives at Ft Worth; Ft Worth, Texas,

USA; Enrollment Cards for the Five Civilized Tribes, 1898-1914;

NAI Number: 251747; Record Group Title: Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs;

Record Group Number: 75

(Also microfilmed as National Archives Publication M1186 Seminole Card #843)

Source: Same as above.

(Close up of image on front of Mahardy card)

The Interviews

The application jackets, contain one of the most complicated cases of identity, belonging, recognition and self identity, and several pages are included here. What appears on the surface by looking at the enrollment cards to be a simple case took many directions as the case of Wyatt Mahardy unfolded.

The outside cover of the file reveals the complicated nature, of the issues contained.

Several pages of letters appear in the front of the file, and I am presenting the "Statement of Case"that summarizes much of the case. Note that the focus was placed upon the son Samuel and the request made by the father to have him removed from Seminole Freedman status to that as Chickasaw by Blood.

Then, the interview begin. Betsey Mahardy points out that she was actually Creek, and thus casting doubt into data that appears about her on the enrollment card. She states that some relatives of her were the ones who had enrolled her as a Seminole Freedman, but she clearly states "No sir, no Seminole Indian ever owned me."

She pointed out that her sister "Ben Bruner's wife" was the relative who enrolled her, but her identity was that as being Creek, and not Seminole. The interview also goes on to inquire about her marriage to Wyatt Mahardy as well as her first marriage that was performed by John Ishtone, a well known Seminole preacher.

It was revealed during the interview that Wyatt Mahardy was now deceased, and had passed only a few months before.

An interesting exchange occurred about whether Betsey was Creek or Seminole. She explained how at the time the war began, she was visiting her sister who was Seminole, then all of them had to leave and go south into Chickasaw country to avoid the war.

Questions about her son by her first marriage then arose, and she explained how she was married to a Seminole, which brought about the question:

Q."What do you mean by saying you was a slave and married to this Indian? A. "Indians has slaves."

Q. "You said you were married to Bruner who was an Indian?" A. "I married him."

She went on to later describe issues about payments and life in the Territory, including whether the children attended Indian school.

A very strong statement of support for Samuel Mahardy came from John Thomas a Chickasaw by blood. He confirmed much of what Betsey had said about their coming into Chickasaw country during the war. He also confirmed that Samuel had attended Chickasaw schools and had boarded with him, while going to that school. He confirmed that Mahardy was always viewed as being Chickasaw. He also confirmed that Wyatt Mahardy had received payments on behalf of the boy Samuel, while attending school, and he, John Thomas has witnessed Wyatt Mahardy receiving payments.

The interview with Samuel Mahardy himself is most revealing, and he tells a fascinating story about himself, his childhood and his identity as a Chickasaw. Having once been given land as a Seminole freedmen he returned the certificates awaiting correction or adjustment to his status as being Chickasaw.

He confirmed that his father collected Chickasaw money on his behalf, and pointed out how his father once purchased red boots for him and a fine saddle for his mother.

The most clear statement by Mahardy and how he identified himself was when the questioning went back to his status as a Seminole. He interrupted the questioner and made a powerful statement:

The entire portion of his interview appears below.

Samuel explains the confusion of how he came to seen as Seminole and his objection from his early years and insisting on his strong identity as Chickasaw.

The young Mahardy recalled how Chickasaw officials came to their home and even spent the night there, took down the names of the family, and he would later learn that their names were stricken from the Chickasaw rolls. Clearly the young Samuel wished to be officially recognized by the tribe where he lived, was a part of his entire life, and was adamant about his being recognized by the officials as part of the community in which he had been a member his entire life.

There were more pages in the file, but the final decision was not made in Samuel Mahardy's favor. His name remained on the Seminole Rolls.

Many times, the issue of whether one is "Indian" or not arises. In this case, clearly Samuel Mahardy was Chickasaw. Not only by blood, but by culture and identity. Yet, he was treated differently because of the "Negro" blood from a grandfather. The current practice of the day to insure that a perceived "stain" from African blood would be his identity, thus enforcing a racially influenced policy of racial "superiority" and a racist "inferiority" to be place on having an African presence.

Betsey would remain on the Seminole lists also though she stated that she was Creek and not Seminole. The nations were clearly close to each other geographically, and contact among people was fluid. The Mahardy family is clearly a family with blended cultures, blood lines, and tribal histories. Theirs is one that reflects a true "melting pot" that was the life of families in Indian Territory, and it is one that can be studied from many perspectives. The Mahardy legacy is richly rooted in multiple tribes, and is one that exemplifies the complexity of life in a pre-statehood land that would eventually become the state of Oklahoma.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

This is the 10th article in a series devoted to sharing histories and stories of families once held as slaves in Indian Territory, now known as Oklahoma. The focus of the series is on the Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, and these posts are part of a project with a goal of documenting 52 families in 52 weeks.