Photo: Courtesy of Oklahoma Historical Society

National Archives Publication M1186

Creek Freedman Card #825

Color image accessed through Ancestry

Creek Freedman Card #825

Color image accessed through Ancestry

(Source same as for above image)

The Davis family of Broken Arrow is a family with an amazingly rich history, and Muscogee Creek culture. Much of the history and rich culture of the family is found apart from the cards above and will be discussed.

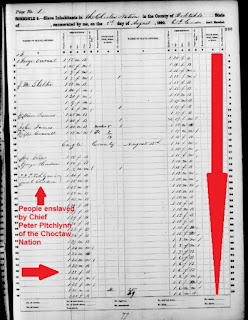

Anderson Davis appeared at the Dawes Commission hearings with the purposed of enrolling his family as Creek Freedmen. He was 45 years of age at the time, but it appears that quite possibly, Anderson Davis was not born enslaved, but was aactually born a free man. However, his wife, Lucinda was born enslaved and she was enslaved by a Mucogee Creek Indian known as "Tuskena" or as she called him, Tuskaya-hiniha.

Anderson's parents were Joseph Davidson, and Becky Marshall. They too were not listed on the card with a slave holder, suggesting that they too were also free born. There were many Creeks who were of African Ancestry, who were born free and lived as free people in the tribe, and it appears that Anderson and his family were among them.

But Lucinda's family was different. She herself was born enslaved, and her parents, were in fact enslaved by Creek Leader Opotholeyahola. From the enrollment card it is also clear that the family members all belonged to Arkansas Town in the Creek Nation, and their story is one that is clearly entrenched in the tribe.

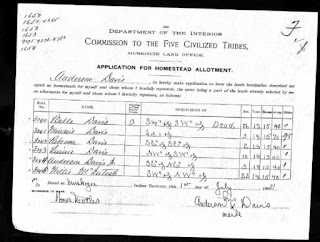

Selection of Land:

Anderson Davis also applied for land allotments for his family and he went through several interviews pertaining to their selection of land. Several records appear in those files reflecting the selection of land and the persons to whom the land would be allotted.

Ancestry.com. Oklahoma and Indian Territory,

Land Allotment Jackets for Five Civilized Tribes, 1884-1934 [database on-line].

Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2014.

Original data: Department of the Interior. Office of Indian Affairs.

Original data: Department of the Interior. Office of Indian Affairs.

Five Civilized Tribes Agency. Applications for Allotment, compiled 1899–1907.

Textual records. Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75.

The National Archives at Fort Worth, Texas.

Source: Same as for above image

Source: Same as for above image

Source: Same as for above image

Lucinda's Story

More can can learned about Lucinda Davis and her life story, because she was interviewed in the 1930s as part of the WPA Slave narrative project. Her interview is one of the most out-standing because of the history and culture that she described in her interview. Though not sure of her birthplace, she was born in the Creek Nation, and her parents were enslaved by Opothleyaholo. But she was separated from her parents, as she however, was sold to an old Creek man, Tuskaya-hiniha.

The WPA Oklahoma Slave Narratives

Editors T. Lindsay Baker, Julie Philips Baker

Contributor United States. Work Projects Administration

Edition illustrated

Publisher University of Oklahoma Press, 1996

ISBN 0806128593, 9780806128597

She describes also the status of Tuskaya-hiniha, within the Creek Nation. He was a man of stature among the Upper Creeks and she provided much detail about her life with Tuskaya-hiniha. He had a daughter whose husband had died, who was living with them. The old man's daughter Luwina had given birth to a baby, and Lucinda, while still a child herself, was purchased to look after the child.

(Source: same as for above image)

Her life as a slave to old Tuskaya-hiniha was well described. He was old and his eyesight had begun to fail. During that time as his vision worsened, some of the other slaves began to slip away and seize their own freedom. She goes on in her interview, wehre she describes her life as a young girl, with no childhood, whose task it was was to tend to other children. When sold to Tuskaya-hiniha, he had poor eyesight and occasionally, once his sight failed, one her tasks was also to lead him around.

Growing up as a Creek, and working inside the home, Lucinda learned how to make traditional dishes. She describes many of them from sofki, to other methods of making corn based dishes

Her description of tasks of slaves who were weavers are interesting to read funeral and burial services were vivid and she described traditional Creek ways of life.

Funerals and Burials

For those with Civil war interests, she was a near neighbor and practically an eye witness to the Battle of Honey Springs. She described how she saw Indians on route to the battle with their gray colored clothing on horseback carrying a flag with a large "criss-cross" on it. She and the old master joined hundreds of others fleeing the battle zone as they headed out onto the Texas road going southward to flee the battle. She described seeing the same gray-clothed soldiers fleeing the battle being pursued by men in blue uniforms in a rapid chase.

She goes on to describe how they got onto the Texas road and headed south. Later they camped and listened to the battle sounds throughout the night.

The most heart touching portion of her story was when she was finally retrieved and taken back to her parents from whom she had been separated for so long. She described the men coming up to the old slave older, speaking in "English talk" and how she was, as a result put on a horse and later met by her parents who had been searching for her.

(Source: All images from her narrative are from the same source listed above.)

There is more to the story of Lucinda Davis. By the time she had several children, statehood approached, and the Dawes Land Allotment process had begun. Her husband Anderson applied for, and receive land allotments for himself, wife Lucinda, and their children.

The story of Lucinda Davis is well documented, but the story of Lucinda as a girl, then the years of her marriage, their large family and their selection of land has never been presented together. She mentions her children in the interview, and that most had died by the 1930s. By presenting her case along with the enrollment cards and land records above, a larger part of the story was known.

Lucinda Davis was a strong Creek woman, and she was a strong African descended woman. She held strongly to her culture, and her mother tongue which was the Muscogee language. Hopefully her final days were peaceful. No information about her death, but her narrative is one to be shared by many who wish to learn about the lives of those seldom mentioned---those once enslaved in Indian Territory. Those who wish to know about the customs of Muscogee people will learn a lot from her narrative, and those who wish to read about a woman who was a survivor from a period that brought much pain, will grow from reading her story.

Thankfully, the details of her life during and after freedom will speak to her resilience and to her fortitude. We should all grow from her strength, and her story.

********** ********** **********

(This is the 9th article in a series devoted to sharing families of those held as slaves in Indian Territory, now known as Oklahoma. The focus is on the Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, and are part of a personal goal in 2017 to document 52 families in 52 weeks.)