For anyone researching Chickasaw Freedmen, it can be a challenge to conduct the research in a thorough manner because in many cases the data was sparse in the application files. However, there are amazing clues to the family history to be found on the Dawes Cards, and by studying the additional members of the family.

Nellie Ligon lived in Pontotoc County of the Chickasaw Nation at the time of the Dawes Commission. She lived in the community of Wiley, I.T., and appeared for the interview on September 27, 1898. She applied for herself and her daughter Caroline Moore, with whom she also resided. She was 60 years old at the time, and had clearly been enslaved in her younger years. She was once enslaved by Chickasaw Elsie Harris, as was her daughter as well.

An interesting notation appears on the card describing the fact that there was a "Nellie Ligon Contested Case."

Ancestry.com. U.S., Native American Enrollment Cards for the Five Civilized Tribes,

1898-1914 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008.

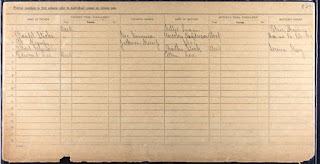

Chickasaw Freedman Card N 827

Chickasaw Freedman Card N 827

From the reverse side of the card, it is noted that Nellie did not provide the name of her father and it was only noted that he was deceased at the time. Her mother's name was Tena Clifton, and she was also deceased at the time. There is no clear indication why the father's name was not mentioned. Considering Nellie's age, it is possible that like some who were once enslaved, the names of both parents was not always known. Nellie's mother Tena, had once been enslaved by Tokolski of the Chickasaw Nation.

Source: Same as above

Thankfully an interview was found in the file. With Chickasaw Freedmen, the commissioners ended up submitting abbreviated files as the final version. They were later interrogated about this practice of submitting interviews as short as 2-3 sentences. The file of Nellie Ligon was a file with some content.

Much of the focus on the file was placed on her status while enslaved and then freedmen. Her movement outside of the territory during the war was an area of focus and the length of time spent living in Indian Terriotory. Like many people enslaved during the Civil war, she was taken south, as a method of preventing any escapes while the turmoil unfolded in the Territory.

Nellie was asked who her owner was before the war, then who the owner was after the war, and whether or not she had been sold. (This was significant because had she been sold to someone in Texas then she may have been made ineligible for enrollment and a subsequent land allotment.)

National Archives Publication M1301, Application Jackets, compiled 1898-1914

Record accessed from Fold 3, Native American Collection,

Chickasaw Freedmen Dawes Packets File #827

A witness was brought in to corroborate what Nellie said about her life as a Chickasaw slave. The witness was John Childers who knew Nellie for many years. He pointed out in his testimony that he knew Nellie had been a slave of "Granny Harris" as he referred to Eloise Harris the slave holder listed on Nellie's Dawes Card. It was recorded that Granny Harris was actually the grandmother of Governor R. M. Harris of the Chickasaw Nation.

Source: Same as for above image

There were additional letters in the file, but no additional interviews, so it was not clear upon first read exactly what the "contested" case was noted in a document above.

At the top of the page of the interview pertaining to Nellie, they would point to the related case. That was the case of her son, Frank, who also lived in Pontotoc, in the same town. Frank applied for himself and his wife Viney, a step son, and two children who were his wards, Turner Cheadle, and Bertie Love.

A note also points out that his status would depend upon the status of Nellie Ligon.

Ancestry.com. U.S., Native American Enrollment Cards for the Five Civilized Tribes,

1898-1914 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2008.

Chickasaw Freedman Card N 864

Chickasaw Freedman Card N 864

Rich parental data is found on the reverse side of the card. Although Frank's father is not listed, Nellie Ligon is identified as his mother. Viney's parents were Randel Sticks and Anecky Henderson. The names of the parents of the step son, and the wards are also listed on the back of the card. Viney's mother was enslaved by Har-no-ta-tubby a Chickasaw. The ward Turner Cheadle's parents were listed and the mother was enslaved by another Chickasaw Serena Gray.

Source: Same as above image.

The application jacket of Frank Ligon contained some of the identical items found in the file of Nellie to that of Nellie, with two significant additions. One was another interview pertaining to Caroline Moore, Nellie's daughter. That interview was significant because all of Nellie's children were mentioned in that series of questions.

The primary concerns with Nellie's case focused on her movement to Texas during the war and the birth of Frank in Texas while she was taken and held there. There was the concern that perhaps she was sold which would have been the technicality to prevent her being allowed to enroll, and to choose her land allotment. In the file was a tender letter written by Nellie explaining her story.

After receipt of her letter and a series of memorandums that appear in the file, a decision in Nellie's favor was eventually made. Thankfully she persevered and was allowed to enroll, and subsequently select her land allotment.

Ancestry.com. Oklahoma and Indian Territory,

Land Allotment Jackets for Five Civilized Tribes,

1884-1934 [database on-line].

Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2014.

Original data: Department of the Interior. Office of Indian Affairs. Five Civilized Tribes Agency.

The file reflecting Nellie Ligon and her family are encouraging for the reflect a woman who was clearly the matriarch of her family face the commissioners in her interviews and to address the status of her family with passion and dignity. Seeing her live to select her land as well, reflects her strength, resilience and devotion to her family.

****************

This is the 13th article in a series devoted to sharing histories and stories of families

once held as slaves in Indian Territory, now known as Oklahoma.

The focus of the series is on the Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, and these posts

The focus of the series is on the Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, and these posts

are part of a project goal of documenting 52 families in 52 weeks.