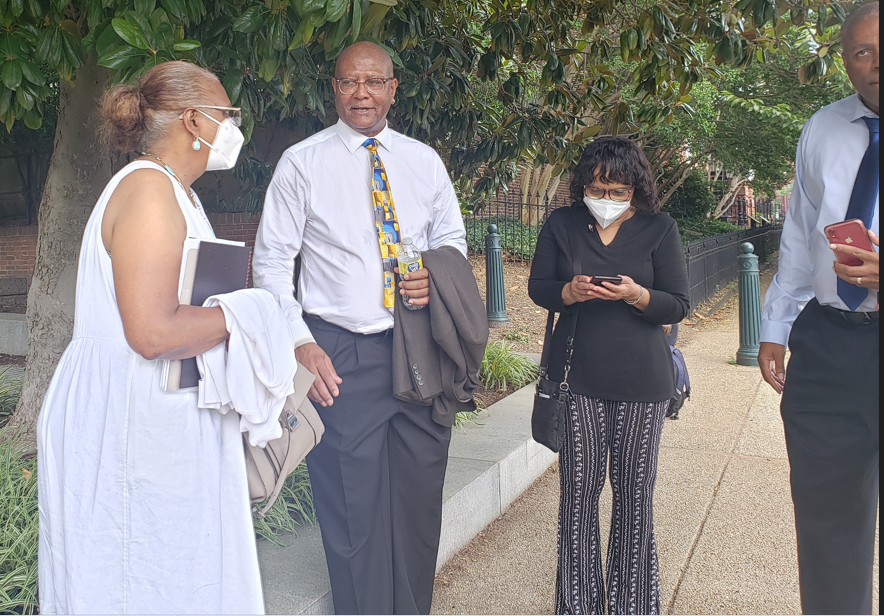

Women (left to right): LeEtta Osborn Simpson (Seminole); Rhonda Grayson (Muscogee); Sharon Linzy Scott (Muscogee), Marilyn Vann (Cherokee), Rosie Khalid (Cherokee); Angela Walton-Raji (Choctaw)

Demario Solomon-Simmons, (Muscogee), Terry Ligon (Chickasaw), Calvin Osborne (Creek)

(This group met in Senator Schatz's office after the Senate Hearing)

On July 27th, the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs met in Washington DC to listen to input from the five slave-holding tribes. These tribes are the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole Nations. The purpose of the hearing was to discuss issues pertaining to the descendants of Freedmen--the African people once held in bondage in those nations. I was fortunate to be able to attend this hearing.

Upon arrival at the Hart Senate building, Freedmen descendants gathered in front of the building before shortly before 2:00 pm when doors were opened. For them, it was an opportunity to meet descendants from other tribal nations, for the first time. Interactions were congenial, friendly, among the small group of descendants some of whom were meeting in person for the first time.

Before the committee convened, all in attendance gathered in front of the Hart building. There was little interaction between tribal representatives among themselves, and the gathering in front of the building was extremely quiet. But for Freedmen representatives all five tribes were present, and this was only the second time since 1866, that Freedmen descendants from all five nations were present in Washington for a hearing pertaining to their status within their own respective nations. The first time was in 2021 when descendants gathered for a hearing in the House of Representatives.

No others were present at the Senate building, except the Freedmen descendants and invited speakers.

No others were present at the Senate building, except the Freedmen descendants and invited speakers.

Choctaw, Chickasaw and Muscogee chatting before hearing

Lto R: Doris Burris Williamson, Terry Ligon, Sharon Linzy-Scott, Calvin Osborne

Lto R: Doris Burris Williamson, Terry Ligon, Sharon Linzy-Scott, Calvin Osborne

Choctaw/Chickasaw and Muscogee

descendants sharing info.

Terry Ligon, and Calvin Osborne

Terry Ligon, and Calvin Osborne

Tribal officials soon arrived, generally keeping apart from others. Some arrived wearing traditional native necklaces and generally awaited the opening of the doors to the Hart building, near the entrance. Most were quiet and not much inter-tribal interaction or talking among each other before entering the Hart building.

Before the Senate hearing

Once the doors opened, the small group of about a dozen of us were directed to the room for the senate hearing once we were cleared and names of invited guests were confirmed. The hearing room contained some large television monitors so that those of us seated behind the speakers could actually see their faces as they spoke.

Freedmen descendants sat behind listening to the spesakers. Only one spoke with honesty and heartfelt sincerity about their history and historical mis-treatment of Freedmen and then offered a sincere apology to descendants. That was Cherokee Chief Hoskins who also mingled freely with Freedmen before and after the hearing.

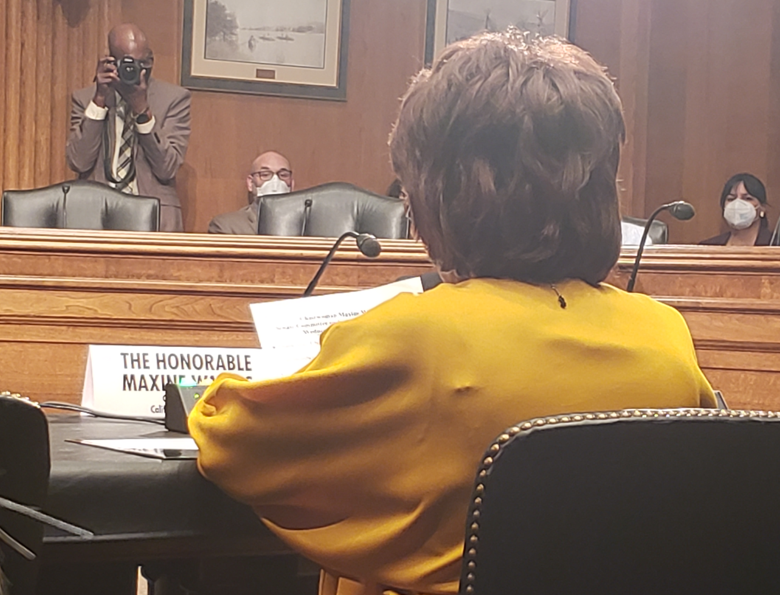

The hearing began with Congresswoman Maxine Waters addressing the Senate Committee. She was then followed by others representing the BIA, and the various tribes. The only speaker on behalf of the Freedmen was Marilyn Vann long time Freedman advocate, and now an enrolled Cherokee citizen.

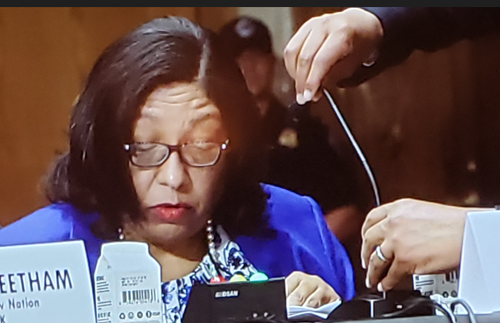

Panelists listen to Congresswoman Waters address.

Other speakers spoke about blood--ignoring that they also prevented Freedmen who were connected by blood to them, from being placed on the blood rolls. One after another they spoke, some never answering the questions asked, and others simply clinging to their security blanket of "sovereignty" as sssomething to hide their race-based biases behind.

The hearing began with Congresswoman Maxine Waters addressing the Senate Committee. She was then followed by others representing the BIA, and the various tribes. The only speaker on behalf of the Freedmen was Marilyn Vann long time Freedman advocate, and now an enrolled Cherokee citizen.

Panelists listen to Congresswoman Waters address.

Other speakers spoke about blood--ignoring that they also prevented Freedmen who were connected by blood to them, from being placed on the blood rolls. One after another they spoke, some never answering the questions asked, and others simply clinging to their security blanket of "sovereignty" as sssomething to hide their race-based biases behind.

Only one voice was heard speaking on behalf of the disenfranchised Freedment descendants. Ms. Marilyn Vann spoke and was the lone voice speaking for Freedmen descendants. Ms.Vann is now an enrolled Cherokee citizen, so technically no voices of disenfraned Freedmen were heard, while tribal officials sent attorneys, ambassadors, and even BIA officials who uphold tribal policies and who also spoke against any concept of Freedmen equal treatment.

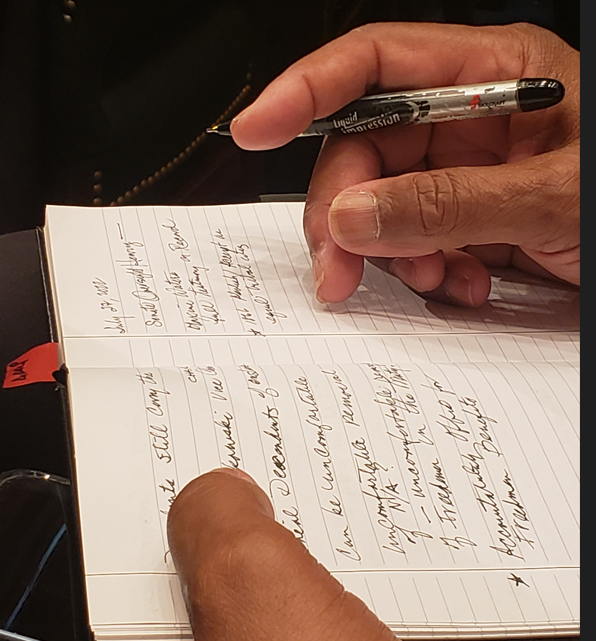

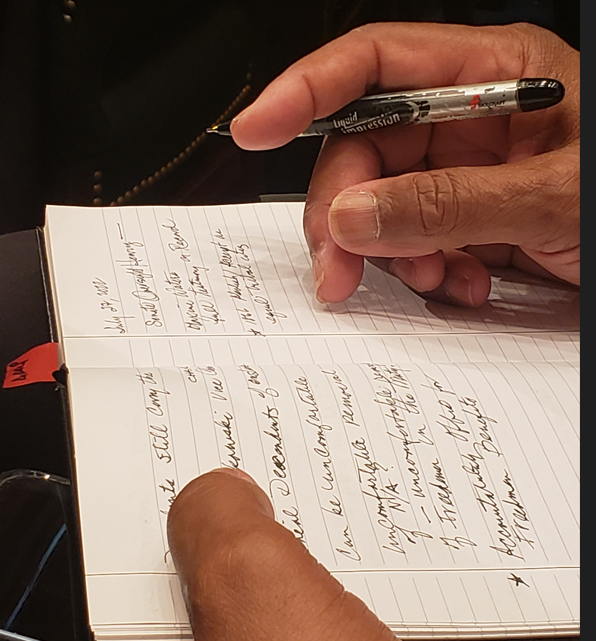

Several of the Freedmen took vigorous notes during the hearing as the panelists spoke.

Note taking during the hearing.

Note taking during the hearing.

After the hearing only a few of the tribal speakers conversed or had dialogue who with Freedmen descendants, and most of them quickly left after the hearing. Later, a smaller group of 9 Freedmen descendants (pictured at the top) from all of the Five Tribes met with Senator Schatz in his office for a brief discussion about moving ahead.

Reflections After the Hearing

Reflections After the Hearing

Moving ahead, today, 156 years after the treaties were signed by each tribe, the descendants of the Freedmen are still seeking justice. Why? Because four federally recognized tribes prevent them from having basic rights coming from their own family ties to them. These nations claim to be "sovereign" nations, while they refuse to offer services to all who are part of them.

Freedmen descendants are those whose ancestors lived with them, were enslaved by them, remained with them when later freed, abided by the same laws created by them, and were part of them. However, today---the descendants of only those who have a certain "blood" are allowed to be a part. Sadly that blood policy also means that if you have a blood tie to a slave, then you are less than they and are to be shunned and forced to remain so--forcing people to carry a "stain" of slavery--a status they never sought.

In Oklahoma today in these nations, educational doors are opened for children, summer camps prevail, STEM educational training abounds, and scholarships and educational grants, are offered, and so much more. There are health benefits for the elderly, housing assistance for those in need, mental health assistance for those also in need, all of which are funded by US Federal dollars.---but the black children have no such access, nor do the elderly black people, many of whom are related to their lighter-skinned enrolled tribal members. Those light to white skinned members are welcomed into the nation, and live with these enriching benefits because they are allowed to have association with the tribe of their ancestors. But the Freedmen cannot have association with the tribe of their ancestors---some of whom are the same as enrolled members. That is the irony and the bittersweet aftermath of American slavery and Indian tribal practice of black chattel slavery.

Today the struggle continues. It is noted that when post Civil-Rights years-- in the 1970s and 1980s these former slave-holding tribes had now embraced the the same "old-south" racist feelings to black citizens, and with the aid of friends and colleagues who had become federal BIA workers. They simply changed their constitutions and quietly removed descendants of slaves from eligibility.

Since then, these same tribes have been able to execute racist policies in the name of "sovereignty" and have been able to ride on national sympathy as victims of the Trail of Tears, bringing in millions of tourist dollars and wealth from casino monies. Their wealth is enhanced by federal funds, and now these slave-holding tribes have become wealthy, large employers, and "good neighbors" to Oklahomans, as long as the neighbors are not Freedmen descended people.

The resilience of the Freedmen from the past is found in the resilience of their descendants today. The fight for equal opportunity continues to fight for the same opportunities that are their birthright. Freedmen never imposed themselves upon tribes it was the tribes that imposed their laws and culture upon them. Today thousands of Freedmen descendants still have a strong identity to the same tribes--simply because that is what they are.

Descendants seek to live full lives complete with the same opportunities that their fellow neighbors, friends and even kin have. This struggle continues because "it is the right thing to do."