One of the Dawes Records Reflecting Part of Don Cheadle's History.

Source: NARA Publication M1186, Chickasaw Freedmen Card No. 729

Many of us recall the PBS Series

African American Lives. The episode reflecting he history of actor Don Cheadle interested many of us who share the history of the Freedmen of Indian Territory. When it was revealed to Mr. Cheadle that he had ancestors who had been enslaved by Chickasaw Indians he was stunned to learn of this history, and mentioned that he had never heard of Native Americans and Black Chattel slavery. Dr. Henry Louis Gates also admitted that this was history of which he himself also had no knowledge.

Meanwhile, dozens of Kemps and Cheadles from southern Oklahoma, from Texas and across the country, in addition to thousands of people who descend from the former slaves of the Five Civilized Tribes--nodded as we watched once again, how so little is known. Amazingly this unique history has over 14,000 records at the National Archives, that tell the story, and yet not even a Harvard professor had heard of the Freedmen of Indian Territory.

In the episode, Mr. Cheadle was told, "You are one of the few African Americans whose ancestors were not enslaved by white people." But the reality is that the numbers are not quite as small as Dr. Gates assumed them to be.

Being familiar with Mr. Cheadle's ancestry and having researched Freedmen for over 20 years as well as having Choctaw Freedmen ancestors myself, I examined the records of Don Cheadle's family. I also had the opportunity to find the Civil War record on his Missouri family. But the Cheadle and Kemp history is a fascinating family history, indeed!

Don Cheadle is tied not only to a large clan of Oklahoma Cheadles---but he is also tied to an even larger clan of Kemps---who reside to this day in southern Oklahoma and Texas and beyond.

As he was told on

African American Lives, his gr. gr. grandmother was Mary Kemp. Mary Kemp had married Henderson Cheadle also known as Hensce Cheadle and they had 8 children, including his gr. grandfather Bill Cheadle. Mary Kemp had been born a slave and was the slave of Chickasaw Jennie Kemp.

Close Up view of Mary Kemp Enrollment Card

NARA Publication M1186 Chickasaw Freedmen # 729

The back of this card reveals more information about Mary Kemp and her children.

Reverse side of Chickasaw Freedmen Enrollment Card #729

The columns on the reverse side reflect the name of the father of each person on the front of the card, and the card also shows if the parents were slaves, the name of the Indian slave holder. So in this case Mary Kemp's father was a man called John Kemp, who was a slave of Chickasaw Jackson Kemp. Her mother was Frances Kemp, also enslaved by Jackson Kemp. Eight of Mary Kemp's eleven children were fathered by Henderson Cheadle--called Hensce.

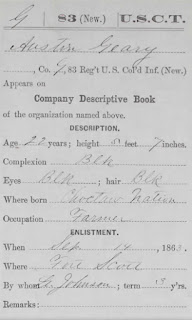

Mary's former husband, Henderson Cheadle himself also had an enrollment card from the Chickasaw Nation.

Henderson Cheadle Enrollment Card

Source: NARA Publication M1186 Enrollment Card Chickasaw Freedman #813

Henderson Cheadle's father was a man called Elderidge Edwards, and his mother was Peggie Edwards. Both of them had been enslaved by Chickasaw citizen Jim Cheadle.

Reverse side of Card reflects the parents of Henderson Cheadle. Though called Edwards, they were enslaved by Chickasaw Jim Cheadle.

Source: NARA Publication M1186 Enrollment Card Chickasaw Freedman #813 (Side 2)

Mary Kemp Cheadle and Henderson Cheadle had separated from each other, and she had remarried. Her second husband was Scott Finley and in their file was a copy of their marriage record.

Marriage Record of Mary Cheadle to Scott Finley

Source: NARA Publication M1301 Dawes Enrollment Packets

Chickasaw Freedman File #729

In the 1900 Federal Census taken in Indian Territory, Mary Kemp Cheadle and her children appear in the Chickasaw Nation community enumerated together. And son, William, gr. grandfather to Don Cheadle is in the household with her.

1900 Census enumeration of Mary Kemp Cheadle

By 1920, William was married with his own family and living in what was now the state of Oklahoma.

William Cheadle and family living in1920 in Oklahoma

Source: 1920 Federal US Census, Oklahoma

Lee Turner Cheadle was William's son, and when the family later moved to Missouri, the family's ties to Oklahoma were broken. Lee Turner Cheadle is Don Cheadle's grandfather, and Don Cheadle Sr. is the son of Lee Turner Cheadle. Don Frank Cheadle Sr is the father of Don Cheadle Jr., the actor.

Of course time did not allow for extensive detail about the lives of those who were enslaved in Indian Territory to be shown in the PBS program that featured Don Cheadle. The lives of the slaves in the Territory have never been widely studied which would explain why Dr. Gates himself knew nothing of this history. But there are still records that tell this story.

Mary Kemp Cheadle was enslaved by Jackson Kemp. What would her life have been like as a slave to Chickasaw Indians?

Jackson Kemp was a large slave holder in the Chickasaw Nation.

Source: 1860 Slave Schedule Chickasaw Nation

Ancestry.com. 1860 U.S. Federal Census - Slave Schedules [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010.

Original data: United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1860. M653, 1,438 rolls.

Jackson Kemp owned 61 slaves in 1860. The oldest was 61 years old and the youngest--were several children 1 year or less in age. On closer examination, at least 20--more than a third of the slaves he was said to have owned---had fled from him. They were listed as "fugitives." Among the runaways was even the eldest slave.

Close up view of Slave Schedule of Jackson Kemp Slaves. The oldest slave was listed as a fugitive.

The presence of so many runaways from bondage suggests that Jackson Kemp may not have been viewed as one of the most kindly of slave holders, evidenced by the resistance of more than a third of his human chattel said to be fugitives.

In addition to simply knowing the names of the ancestors of Don Cheadle, there also comes a fascinating history of the Kemps. Mary Kemp the matriarch of the Cheadle clan, had an older brother Isaac Kemp. Isaac Kemp was leader and an activist in his community of Chickasaw Freedmen, He worked with a group of other leaders to speak on behalf of Chickasaw Freedmen. Their treatment and their neglect by the Chickasaw Nation, as well as the US government was a issue for more than four decades, and both Kemps and Cheadles and also the Loves were among the leaders of Freedmen that continually fought for the rights of the former Chickasaw slaves.

This item is a document from the National Archives (II) found in a box of miscellaneous letters reflecting issues pertaining to Chickasaw Freedmen. Included was an item from Isaac Kemp a leader

in the Freedman community of Wiley, I. T.

The saga and struggles of the Chickasaw Freedmen went on for many years. Scholar and professor Daniel Littlefield wrote about them, in his book The Chickasaw Freedmen, and some of Don Cheadle's ancestors were noted in his work as well, including Isaac Kemp--Cheadle's gr. gr. gr. uncle.

The Chickasaw Freedmen by Professor Daniel Littlefield captures the story of hundreds of Chickasaw Freedmen from the years after the Civil War, up to Oklahoma statehood in 1907

Littlefield, Daniel, The Chickasaw Freedmen. A People Without a Country,

Westport Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 1980, p. 166

Isaac Kemp worked alongside other Freedmen leaders to voice their concerns for the educational needs of their children, and when they felt that strong teachers were not in place, they also voiced their concerns about the strength and competency of the teachers as well. In this next excerpt, Isaac Kemp (Cheadle's 3rd gr. uncle and Hensce Cheadle (his gr. gr. grandfather) voiced complaint with others about the status of the schools for Freedmen children.

Source: Monthly School Reports. November 1882, Turner to Price, January 8 and 27, 1883, and

Miles to Commissioner February 8, 1883, Letters Received, 22294-82, 634-83, 1074-73

Isaac Kemp (Don Cheadle's gr. gr. uncle) began his fight for justice immediately after the Civil War. In a rare letter written in 1865, Isaac Kemp's name appeared in a letter to the Arkansas Freedman's Bureau. The letter was asking for help for their loved ones still being held in bondage by the Chickasaw Indian slave holders. I wrote about this letter in a

blog post back in 2010.

At the end of that letter the "X" marking the signature of Isaac Kemp is found. He was requesting release of his wife and children, and also of his mother Frances (3rd gr. grandmother of Don Cheadle). This was probably the first time that Isaac Kemp's name appeared in writing as a free man. It was also perhaps the first in many battles that he would fight and that would initiate a battle for justice in Chickasaw country.

Isaac Kemp's mark is shown among the signatures of others seeking freedom

for their loved ones in the Chickasaw Nation.

Programs such as

African American Lives as well as the NBC program

WDYTYA (Who Do You Think Your Are) now in its third season, are popular and they encourage many to explore their family history. However, what is often shown on the prog, rams are mere glimpses as their history.

As the case of Don Cheadle, his Chickasaw Freedmen history is rich, complicated, colorful, and also inspiring. The few moments aired on the PBS program only mentioned the Chickasaw Freedmen, but as one can tell, there is so much more to this amazing story. As one who researches the Freedmen of Indian Territory, my hope is that others will be inspired to tell the stories that come from this little known chapter in America's history.

Ancestral Family Tree of Don Cheadle, Descendant of Chickasaw Freedmen